"HFC magic" leads to a role in making the highest-grossing documentary of all time

Kurt Engfehr believes his entire career in filmmaking is an accident. A happy accident, perhaps, but an accident nonetheless.

After graduating from Trenton High School in 1980, Engfehr didn’t know what he wanted to do, so he spent the next three years working as a waiter and for a mortuary service. In 1983, he enrolled at HFC, where he met Jay Korinek, the (since retired) telecommunication professor/program coordinator, who sparked his interest in TV and film.

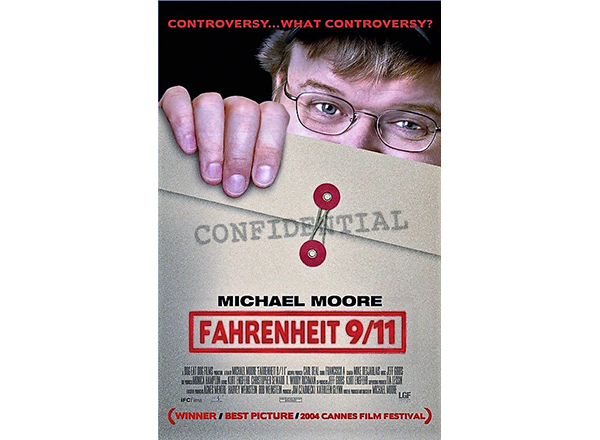

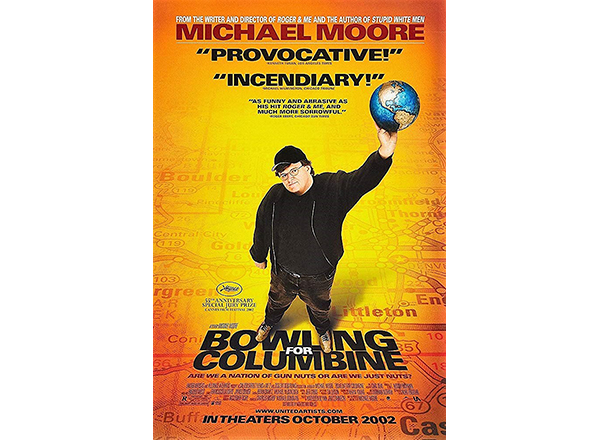

“I never picked up a camera or had any inkling of TV or film as a career, or even as an entity, until I got to HFC,” said Engfehr, who lives in Caldwell, NJ with his wife and fellow filmmaker Elizabeth Marcus. Engfehr worked on Flint native and controversial filmmaker Michael Moore’s two top-grossing documentaries: 2002’s Bowling for Columbine and 2004’s Fahrenheit 9/11.

“I took the 'writing for media' class that Jay taught," says Engfehr. "I also took rhetoric and creative writing. The TV production class was filming what we wrote in the news-writing class. I was surprised and intrigued when the things I was writing in my class would be filmed in the other class. I hung out with the TV production class one day and I thought, ‘Oh, I like this.’ That was it. I fell into the TV vortex, and 30 years later I haven’t come out yet.”

Through HFC, he interned at Channel 56 in Detroit. With fellow HFC alumnus Chuck Miller, he moved to Chicago to attend Columbia College. When he had to drop out due to financial trouble, Engfehr kept in touch with many of his peers in the TV/film program and even sat in on classes. He found work for a small video production company, which filmed weddings.

“I filmed more than 100 weddings in under three years,” recalled Engfehr.

Non-linear and traditional editing

Engfehr answered a job ad in The Hollywood Reporter, where he duplicated video tapes for news broadcasts across the nation in Los Angeles. From there, he found work as an editor on Totally Hidden Video, FOX’s hidden-camera series that aired from 1989-92, and later The Playboy Channel, which he called “a weird job.”

After he “slogged around” L.A. for several more years, Engfehr went to New York City and worked as an editor for the National Video Center, a video production company. One of its clients was MTV in its infancy. The 1982 comedy Tootsie included some scenes filmed at New Video’s headquarters on West 42nd Street.

At National Video, Engfehr learned the difference between traditional editing and non-linear editing:

* Non-linear editing: Engfehr called it “word processing for visual images.” You move images around in any sequence or any order by clicking it, dropping it, and dragging it.

* Traditional editing: Recording a sequence of shots followed by other shots. “It’s a big hassle to change something, because if you do, you have to change all your work.”

Engfehr worked as a non-linear editor for National Video until late 1995. Some of his clients included ESPN, MTV, HBO, and MSNBC.

“It was unbelievable that I got to work with all these high-powered people and networks,” he recalled. “MSNBC was just starting out. When they went live on the air for the first time (in 1996), I went with them. Then I went to HBO after MSNBC as a staff non-linear editor for two years. Those are the people I’m still working with today.”

Meeting Michael Moore

At HBO, Engfehr learned of an opening on Moore’s 1999-2000 TV show The Awful Truth, a satirical series that emulated the format of TV newsmagazines like 60 Minutes, exposing problems in American society, government, and business, often through outlandish sketches and humiliating tactics to point out the inherent absurdity of a situation and hint at potential solutions.

“I loved (Moore’s) TV Nation and Roger and Me. I was a huge fan,” said Engfehr. “I like how he combined humor with serious material. He managed to make horrible things or important things or informational things funny.”

Given Moore’s Michigan roots, Engfehr reworked his résumé to reflect his work when he was in Detroit. According to Engfehr, Moore took one look at his résumé and said, “Trenton, huh? McLouth Steel,” referring to the now-defunct steel company that had been headquartered in Trenton.

“We hit it off real well. We chatted about our dads working at plants – his at AC Delco (in Flint) and mine at BASF (in Southfield).”

Engfehr was hired as an editor on The Awful Truth, where he stayed for one season. He called it hard work, but also a “very, very, very rewarding experience.”

Still, Engfehr continued working with Moore, serving as a producer on Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11.

Downriver and HFC magic

Engfehr says Moore was supposed to finish Columbine in four months so he could enter it in the Toronto Film Festival. Not surprisingly, it was way too big an undertaking, and four months suddenly became 18 months. After the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, Moore altered the documentary to reflect the new reality. Engfehr, Moore, and three others worked day and night to recut Columbine.

“He’d say to me, ‘Kurt, we need your Downriver magic here,’” recalled Engfehr. “I felt like I was back at HFC. It was fun and exciting because we worked on something that had the potential to be really important. We were doing it to entertain ourselves, and it ended up becoming this really amazing movie.”

Moore entered Columbine – which chronicled the causes of gun violence, particularly the 1999 Columbine High School massacre perpetrated by Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris – in the Cannes Film Festival in 2002. At Cannes, it received a 13-minute standing ovation. The documentary was a critical and commercial success, elevating Moore’s profile. Considered one of the greatest documentaries of all time, Columbine won many awards, including an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

“It was the first film I cut and edited,” said Engfehr. “I went from being a TV promotions editor to cutting an Oscar-winning film. That’s how life happens. Weird.”

Moore outdid himself two years later with Fahrenheit 9/11, an intensely controversial documentary where he took a critical approach toward President George W. Bush, the 9/11 attacks, the war on terror, and its coverage in the media. When the film debuted at Cannes in 2004, it received a 20-minute standing ovation – among the longest in the film festival’s history. It grossed more than $222 million worldwide, becoming the highest-grossing documentary of all time.

“Moore’s one of the funniest, smartest guys you’ll ever meet,” said Engfehr. “His projects are hard. They have hard deadlines. They wear you down.”

Blazing his own path

Engfehr has since branched out on his own, co-producing, writing, and editing numerous films – mostly documentaries – such as Bigger, Stronger, Faster; Trumbo; A People Uncounted; Reject; Just Do It; Wrenched; and Red Army.

He later co-directed The Yes Men Fix The World, which won the Audience Award at the Berlin Film Festival and aired on HBO. He also directed Fat, Sick & Nearly Dead, a humorous documentary about weight loss and self-realization that was released theatrically in 2011 and has since become an online sensation, having been viewed by more than 20 million people and spawning an online community of more than 1.25 million people.

In the last three years, Engfehr became creative director for Reboot Media, where he wrote and directed Fat, Sick & Nearly Dead 2 and The Kids Menu.

The Maltese Falcon and the HFC influence

Engfehr directs a lot of credit for his success to his time at HFC.

“I loved my time there,” he said. “(Korinek) set me up for how to do things in the real world, which is different from how you do things in college. It gave me the freedom to experiment and take risks. Those were good times.”

And experiment and take risks is exactly what Engfehr did, according to Korinek. In the film production class, a major project was shooting a 30-minute, undated, abridged version of the 1941 Humphrey Bogart classic The Maltese Falcon. Engfehr was the primary screenwriter, editor, and director.

“We shot on more than 12 locations in the Dearborn area over a four-day and night period, while the editing took another two months,” said Korinek. “An outstanding student needs an unrestricted creative imagination, technical skills, and perseverance, which will lead to career success. In Kurt’s case, he also brought a wild, pointed sense of humor and social concern that ended up making him especially valuable to Michael Moore.”